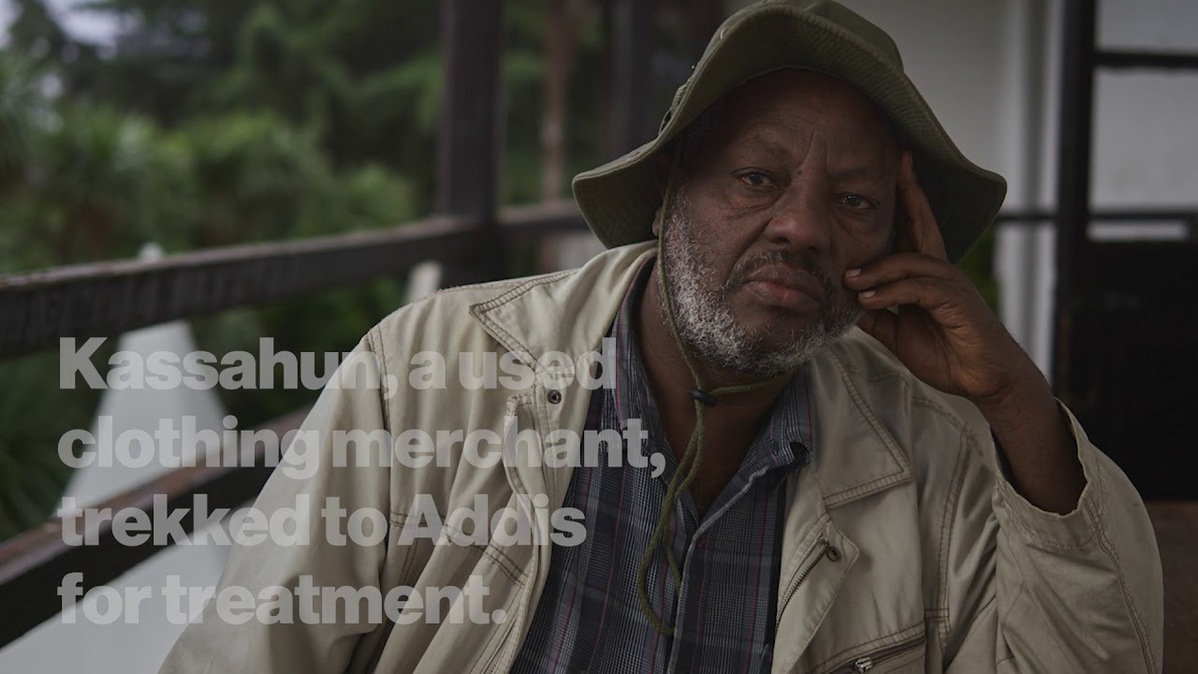

For Kassahun, a used clothing merchant in Ethiopia, managing his diabetes is something of an obstacle course. In the rural area where he lives, there are no doctors specialized in treating the disease, which if poorly managed can spark a host of other health problems, including heart disease, vision problems and nerve damage. So Kassahun travels 300 kilometers (approximately 186 miles) by public transportation to the capital Addis Ababa to see a specialist at the Black Lion Hospital, requiring him to spend several nights in a hotel.

“If we had more skilled physicians in the regions, it would be a relief to us,” he says.

Kassahun’s experience illustrates a major challenge in Ethiopia and many other lower-income countries: There is a shortage of health professionals capable of diagnosing and treating people with chronic illnesses such as diabetes and heart disease. To help address the problem in Ethiopia, the federal government, in collaboration with the Tropical Health and Education Trust (THET) and Novartis, is training doctors, nurses and community health workers to screen patients for common chronic ailments and provide treatment – particularly in rural areas, where 80% of the people live.

“We’re trying to make sure people don’t have to travel to Addis Ababa to get basic treatment,” says Thu Do, who oversees the collaboration for Novartis Social Business. “This is taking care of patients closer to home and reducing their out-of-pocket costs.”

The need for better care is great, and growing. Changing lifestyles and aging populations worldwide are driving increased prevalence of chronic illness. For instance, the number of people with diabetes worldwide has quadrupled since 1980. Low- and middle-income countries account for more than three-fourths of all deaths from chronic diseases, and 85% of premature deaths, according to the World Health Organization.

Yet there is a shortage of health professionals able to treat chronic diseases. In Ethiopia, for example, with 3 million diabetics, only seven doctors are specialized in the disease and only 22% of all health facilities are ready to provide diabetes treatment. As a result, people with chronic ailments often become gravely ill before they are referred to a hospital.

Most of these patients arrive with disease “in an advanced stage and with irreversible complications such as blindness, renal failure, stroke and heart failure,” says Dr. Yoseph Mamo, THET country director in Ethiopia. “Many of these prematurely disabled and dying patients could have been detected earlier and would have lived longer if we had screened them early and started treatment immediately.”

Many of these prematurely disabled and dying patients could have been detected earlier and would have lived longer if we had screened them early and started treatment immediately.

Dr. Yoseph Mamo, THET country director in Ethiopia

To help increase the number of healthcare workers able to diagnose and treat common chronic diseases, in 2018, THET drew on 20 years of experience to launch a training program in Ethiopia with funding from Novartis and support from doctors from the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom. The program focused on workers at 15 hospitals and 45 health centers designated by the Federal Ministry of Health.

The program uses a train-the-trainers approach and began with preparing 30 master trainers from 15 facilities. Since the program’s inception, this core group has trained about 400 additional health workers. They in turn have screened some 40 000 people so far, identifying about 10% of them as having a chronic illness and referring them for treatment. Most were diagnosed with hypertension (high blood pressure) or diabetes.

“I think the community has benefited from this project,” says Deme, a health officer at the Kotebe Health Center in Addis Ababa. “A year ago, people were not being screened at the community level and the service was more focused on treatment rather than prevention. Now, the quality of chronic disease treatment has improved, and the community has become more interested in using the service.”

Much work remains. The next step is to train community health workers, who are on the front line of care in communities. And the longer-term goal is to screen 300 000 patients.

There are also challenges to overcome. For example, staff turnover is a major issue, particularly in rural clinics, with trained healthcare workers moving to new jobs in search of a better quality of life. A possible fix may be nominating one person in each rural location to become a leader who commits to staying, or at least to passing on his or her knowledge to colleagues before moving.

Another challenge is convincing health workers to maintain detailed patient records, which are entered into large books and can help measure the impact of the program. Record-keeping takes about 15 minutes per patient, and some workers see it as taking away from the time they have to care for people. THET is working with the government to try to streamline record-keeping and is advocating for adoption of an electronic health records system.

Programs such as this one are helping to strengthen Ethiopia’s healthcare system and equip healthcare workers to identify and treat people with chronic ailments before their illnesses become acute. This will also help spare people like Kassahun the lengthy, costly journeys they must now take to get care.

Watch the inspiring story of Dr. Helen Yifter, who has devoted herself to improving the care of people with diabetes in Ethiopia.

VIDEO

VIDEO